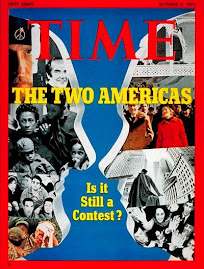

1975: Can Capitalism Survive?

Looks like this isn't the first time the doomsayers of Capitalism's demise have raised their collective voices. Here's a cover story article from the 7/14/1975 issue of Time.

---

"An angry god may have endowed capitalism with inherent contradictions. But at least as an afterthought he was kind enough to make social reform surprisingly consistent with improved operation of the system."

John Kenneth Galbraith

“…Capitalism, Marx reckoned, would pour out more goods than workers could buy with the paltry wages that the system paid them. Wages might rise during a period of expansion, but that rise would cut into profits, leaving capitalists with too little investment money to keep the boom going, and the machine would falter into a slump.

Big capitalists would seize the opportunity to slash wages, buy up the plants and machinery of their ruined brethren and get the boom going again, but the cycle would repeat itself, leading to a worse crash. Eventually, ownership of the means of production would be concentrated among so few capitalists that they would be ripe for overthrow by a proletariat driven by increasing misery into revolution.

Though the apocalyptic prophecy was spectacularly wrong, Marx did point out two highly vulnerable areas in the system. His theory of capitalist concentration anticipated the rising power of large corporations, which can stifle competition and raise prices even in periods of weak demand. More important, Marx heralded the terrifying and prolonged depressions of the 1870s and the 1930s, which classical economics said the self-regulating market would never permit. The nightmare of the 1930s for a while threatened to give Marx the final word.

Fortunately, the Great Depression also inspired the most significant theories of John Maynard Keynes, the British economist who has often been called the savior of capitalism. Keynes insisted that a government could get the free economy moving up again by pumping in purchasing power—through tax cuts, heavy spending and the outright creation of money. Then production would increase, generating more savings, which would be invested. His prescription worked—though it took Government spending on the previously unimaginable scale of World War II to end the Depression. (Keynes also said that tax increases and spending cuts could help contain inflation, but popularly elected governments have seldom been brave enough to follow this part of the Keynesian prescription.)

Since World War II, all capitalist governments have become enthusiastically Keynesian. None would dream of leaving a depression, or even a severe recession, to right itself. By winning acceptance for the idea that government is responsible for the health of the economy, Keynes promoted a degree of state intervention into the market that has helped transform capitalism in a way that Smith never anticipated.

Keynesian philosophy accelerated the trend toward progressive legislation, which had been building in the U.S. since the days of the early trust busters and Teddy Roosevelt, and inspired a bewildering complex of interventionist policies. U.S. companies and entrepreneurs, for example, are restricted by banking and stock market regulations, antitrust prohibitions, consumer protection and antipollution laws, "affirmative action" programs that aim at forcing the hiring of more blacks and women, to name only a few measures. The poor who cannot sustain themselves in the market get Medicaid, welfare payments, food stamps.

Not all of this Government intervention has been beneficial, of course, and some of it has been downright harmful. The operations of federal transportation-regulation agencies, in particular, have often propped up prices and restricted competition. But this complex of laws has on the whole made capitalism both more humane and more effective…”

Read the Time cover story from July 14, 1975.